Dialogues on Infrastructure

The following is an elaborated transcription from an in-person dialogue on Infrastructure. For a more navigable version of this content, see this Notion page.

This session is going to be an open conversation. I’ll first seed it with my own thoughts from my own discipline, and will then open it up for others to share what infrastructure means in their personal field.

Objectives for a dialogue on Infrastructure

How can we take people from different disciplines and together speak to what infrastructure means in our own experiences, from our own backgrounds? My goal here is to connect the dots. Ideally, this session is for you to take thoughts back into your own day to day— to apply new perspectives to what you’re wrestling with. For me / the speaker, the benefit is to hear your thoughts and comments and—if useful— to then weave and integrate it into what I’m doing personally.

The background

To start with some background about why I find infrastructure so fascinating: I come from a civil / environmental engineering background and then worked in green buildings in China for many years. These days, I’m work on the downstream technologies side, in partnership development for a software-based company that integrates into existing building systems to allow occupants to better control their space, especially in non-residential areas where ownership becomes very interesting.

My interest in Infrastructure Across Disciplines has come up in several ways. For one, I’m fairly new to software. Given my civil engineering background, I always felt that infrastructure was “my” word. Then I moved to the Bay Area and all of a sudden I hear it being used all over the place… all throughout software. WHAT?! It took me a long time to grasp an expanded meaning of Infrastructure, with the realization that really it is a shared meaning. To me, infrastructure is the underlying foundation of organizations and systems that enables things to persist and grow.

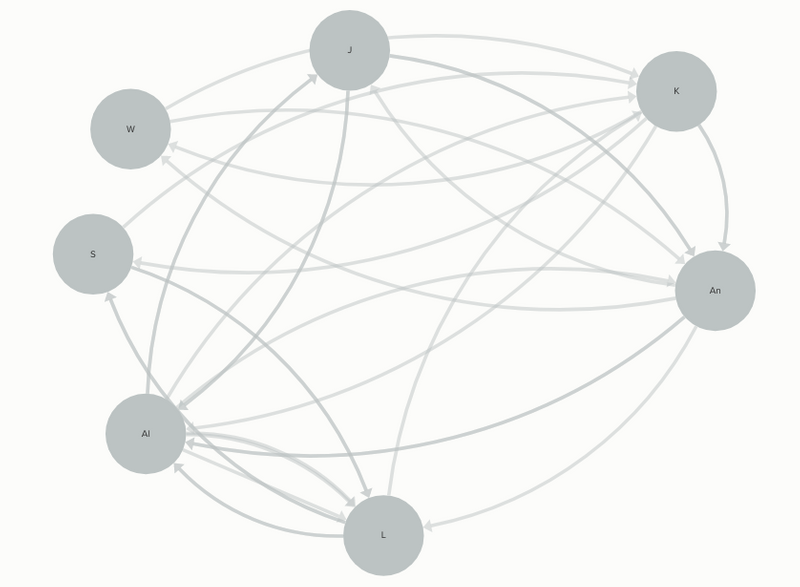

The main participants

October 2018 session

- Liz, technology for buildings [Facilitator]

- Anton, economic history

- Jacob, machine learning

- Katherine, computation / art / interfaces

- Alec, learning + school building

- Sasha, medicine + mathematical biology

- Will, consulting

What is Infrastructure

I believe that infrastructure is the underlying foundation of organizations and systems that enable things to persist and grow. This is similar to the ideas that Anton was mentioning earlier… i.e., that there were important, informal institutions during the Industrial Revolution that fostered the expansion of ideas. I totally see this as infrastructure.

Let’s get started.

What’s to come? I’ll start with a 15 minute story of where I’m coming from, and then open it up to conversation from there. BUT FIRST— I’m going to do an activity because it’s late in the day. Everyone please stand up. (I promise no Turkish Get Ups. Really, you all just looked really sleepy, so I wanted us to stand.)

So: Recall a moment when you were in a building and the actual physical experience of it was amazing. Just like… think about it… what was that like… where were you… what were the factors of why you were there… what made it such a great experience…

And now: Think of a time you were in a building where the experience was terrible. How was it awful, why was it awful, and what did it further impact?

The Seed

What is infrastructure in the buildings industry?

For me, when I think about infrastructure in my industry— again, first from a background of engineering design for a building to now the technologies that go into that building— I see infrastructure from two lenses:

One is the actual control of the environment. So, both the ability for an individual to control pieces of the built world and have information about it, that can help that individual influence her further decisions about where she wants to be, and about how she wants to make use of the space. As a society, our ability to control and condition the environment allows us to spend more time thinking, experimenting, creating, staying healthy.

The other lens is the agreements by which buildings are actually built… but then not just built, to then be occupied and maintained. (Note that I come from a background of high rise commercial buildings, not residential homes.) How buildings are built is often very separate from how buildings are then maintained. We call a building a building, and yet, once it’s been built, it doesn’t continue to be built, it is already built. Why then does the word deserve an “ing”?

Useful framework: Geoffrey West’s 3 postulates for networks

There’s a framework that Geoffrey West lays out in his book Scale that I’ve found to be very influential. It has really informed my thinking on this idea of infrastructure, and I continue to come back to these three postulates of networks.

According to West, (1) networks are space filling, (2) the terminal units— whether capillaries or electrical outlets— are invariant, i.e. they’re always the same size, and (3) systems evolve toward an optimal state.

If you think about the body— say you harm yourself and have a deep wound, that wound heals. It takes some time, but your body adapts. And yet for a building (especially one with multiple tenants were the ownership structure is stratified) this is not the case. Let’s consider the space that we’re in right now. Say that the old tenants move out and we now move in and want to make changes… it is often very difficult for us to do that. I’m not referring to the structural efforts like changing a wall or re-arranging new outlets. I mean it often becomes difficult for us to adapt a space because we do not have the correct information about what is in our space in real life, and who is accountable for it. The building does not adapt in the way you might expect. And I suspect that the way we have organized the creation process of buildings is a reason for this.

On the topic of environmental control & experience

The built environment has a huge impact on how we engage with the world— how we create new ideas, and segregate others. And yet, there are so many ways that we, at this point, take buildings and the systems within them for granted. Just think– we can now live in Dubai because of air-conditioning. We can live now in Florida. A perhaps more obvious achievement is lighting , top of mind given the recent Nobel Prize. How has the accessibility and affordability of lighting acted as a simple enabler to catalyze “progress”?

Over time, complexity increases. I’ll give an example. About a year ago, my company moved into a WeWork. WeWork tends to lease floors in a building as a tenant, and then build really, really fast– retrofitting the space so they can move on to the next one. The sooner they can open, the quicker to revenue. But if you actually look up— which we tend to not do very much but I like to do it often— for all the little offices, all the conference rooms they’ve built out… they do not match at all with the systems in the ceiling, like the HVAC system. This is because: unless they’re making changes to the core and shell of the building they are not mandated by code to do much to the base building layer. Over time, as new tenants come and go, this results in the base building systems not matching the tenant layout. HVAC does 3 things: (1) heating and cooling, (2) maintain pressurization of the building, (3) provide minimal air quality, but it’s typically a base building system. When it doesn’t match the tenant layer, you end up with negative impacts like temperature issues for occupants or unnecessary energy use.

Rethinking Infrastructure

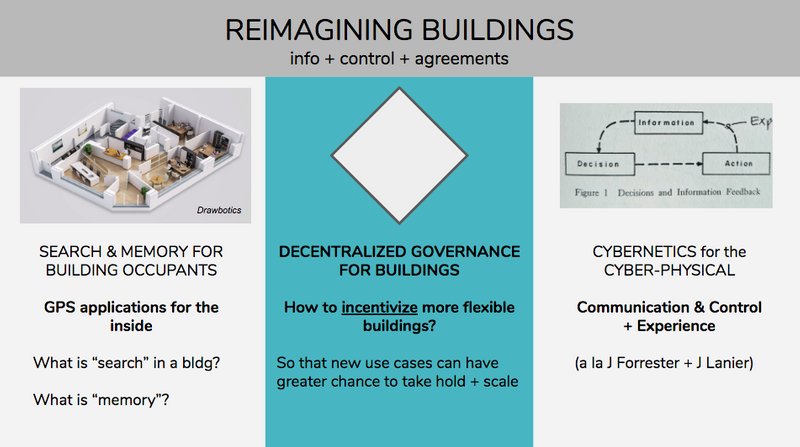

When I think about reimagining infrastructure in my discipline, I think of: how can we re-organize the agreements structure that ultimately impacts the information, control, and experience of occupants in a building. There is so much lost potential. I believe that because buildings are so inflexible, this limits our ability to scale new and significant ways to interact with our built environment and the systems dependent on them… like scaling Dynamicland to reach more people, encouraging more innovation in air-conditioning, or deploying more built-environment solutions to address public health.

Can we rethink the way that these project delivery teams are incentivized such that an architect might actually capture value if someone down the line were to make a change in the building… incentivizing more flexible buildings? What is the version of a quickly updatable building that would allow new and useful systems to be readily deployed?

Just to clarify, I think there are two different ways that a building can be flexible.

One way is where the building is intentionally built to be real-time flexible. Where it’s easy to move walls around, or convert a big space into a smaller space, or, in the example of MIT’s Rad Lab, the occupants have free reign to do what they please.

The second way—the one that I’m trying to explore here— goes beyond that. How can the agreements for how a building is built and maintained allow for greater flexibility? In my real-time flexible walls example… what if a school now comes into that space and doesn’t want those walls to move? Now expand that to think of a multi-story building where you have lots of different tenants, who are changing over time. You end up losing the documentation necessary for the structure and the systems within the building; it doesn’t match what we ultimately see in real life. How can you incentivize the players in the value chain to ensure that there’s some “ground truth” to what ultimately is built and then continues to persist in real life, so that when a tenant or occupant down the line wants to make a change, they can have all the information they need to make the best decision? This documentation is necessary to make the best change possible, in the shortest amount of time, with the least amount of wrangling burden.

The Conversation

Machine learning and norms of dissent

- Jacob: In the academic profession, you can talk about conceptual infrastructure and you can talk about the actual lab equipment. For machine learning, on the hardware side… it’s GPUs. There’s a lot of special purpose hardware architecture built for training neural nets. This basically locks in deep learning at a local maximum. Something else would need to be much better to change this.

- Jacob: Conceptual infrastructure is harder to point to… but an example that comes to mind is norms of dissent. For example, when you write a paper– there are certain expectations. Currently almost all abstracts of papers are dishonest, but there are certain norms around how dishonest an abstract can be. This is kind of like cultural infrastructure. You can be confident that a paper will not be more than a certain amount dishonest if its written by someone who still has good standing in the profession. You’re allowed to be x dishonest but not more. This isn’t codified anywhere, but it creates shared expectation that helps us sort through papers.

Lock-in and railway gauges

- Anton: I can relate to this idea of lock-in personally… I was thinking about plugs and how terrible American plugs are.

[Pulls plug adapter from pocket.]British plugs are so much better. No sparks. It needs the earth to go in, and once it reaches that point of being covered, only then does it open. Safety wise, its so much better. This allows British electrical appliances to be at much higher voltages. Which allows for a lot more stuff as well.

- Will: Yes, this allows British tea kettles to boil water so much faster; it takes so much longer in the US. And that’s why I’m sure the adoption of tea drinking in the US is so minimal.

- Audience: That’s why! Soon you’ll see the tea lobby lobbying for better electrical outlets.

More lock in stories from the crowd:

- Space shuttle to railways

- Battle of the gauges

- Anton: It’s only when the guy who invented the broad gauge died that the other gauge type was able to take over. Only when he died could they supplant his rail system…

- Liz (added comment): This reminds me of something related to longevity. Think of the social implications as people’s lifespans increase. The paradigm of power shifts due to someone’s death in old age will change.

Standardization: pitch & timePitch standardization

- Mid 20th century: whole world agrees on international standard for pitchTime standardization

- With railway came time standardization

- Japan abolished old time system with new railways and establishment of factories

Layers of abstraction: Nouns & Verbs

- Alec: So for us, there are two things that come to mind when I think about infrastructure. One of the things we’ve been thinking about (when building our new school) is: what are the Nouns and Verbs we want to be responsible for? There’s a certain layer of abstraction in infrastructure for us, especially regarding what we do and do not want to own. For example, think of something like enrollment. There are a lot of things that have to happen to get to that point, you can’t just come into a district and be enrolled. There are vaccination forms, contact information… a lot of stuff has to happen. We’ve needed to make decisions around which things we want to be responsible for and which things we don’t want to be. So we can focus on the other stuff that we’re better at doing.

- Liz: How do you decide which things you want to be responsible for vs. not?

- Alec: Our past 2 years of work has been mostly dealing with bureaucratic, legal, and financial hurdles when trying to create a new kind of school. So, we’ve been thinking a lot about the ideal interfaces between us (the school) and the city. The choices that we make about what to vertically integrate or internalize vs. not are often driven by what experience we want for our youth. For example, we want to give our staff, maybe even students, credit cards. The conventional way of thinking within schools is procurement with long bid cycles. The challenge is thinking in these new ways.

- Alec: This becomes infrastructure for our staff. I don’t want our staff to have to deal with it. I (on the administrative side) want to deal with it. Similarly, and related to space… We’ve also been thinking about what data do we want to collect just by virtue of things happening, so that when it comes time for quarterly design charrettes, we have data to influence those designs. No one’s job is data collection analysis. The question we really want to ask is: How is X working? Not taking a quarter-long process to just figure out what information to collect.

- Jacob: I like your framing of infrastructure as something the system designer is thinking about.

- Alec: It feels very related to clean interface abstraction. What’s changing vs. what I don’t want to change. Standards and abstraction are very similar to this.

- Liz: Would you say that infrastructure should be in the background then?

- Alec: For someone it should be in the background. For someone who is building on that infrastructure, it’s not. There are returns to standardizing something at scale. We think of it in terms of the time that someone doesn’t have to think about it. What are the tools that we can choose to provide to people.

Shared language, efficiency vs. universalism, and challenging standards

- Katherine: I’m starting to hear some articulation of infrastructure as a common context or shared interface. And that brings to me an idea that I’m really interested in, which is common language. I work on a very interdisciplinary team. For us, our infrastructure is a common language that we build to talk about our ideas. How do we maintain that context? The people involved are across programming languages, computer graphics, HCI, education, mathematics, etc. In the beginning when we first started the project, it felt that we were just talking past each other. The Programming Languages people would go on about lambdas and type sets. And the Graphics people would talk about meshes and polygons. Everyone was very confused. But as we kept talking, we began to develop new words that were at the intersection of both. For example: the generic idea of how to construct a shape. Programming languages people would say “object” and “instance”. The Graphics people would refer to the idea of “graphical primitives”. So we combined them, into GPI, or “graphical primitive instances,” which straddles both. Of course, now we’ve invented our own new jargon. That’s a different story. But for anyone who joins the project… once they understand our language infrastructure, it’s much easier conceptually.

- Anton: What I’m hearing is this inherent tension between efficiency and universalism. The jargon that you develop for your own project is going to be specific to your project, but hopefully it can become more universal as well. I was struck when you (Alec) mentioned the different Nouns and Verbs that you want to use. Like, that is great for a particular project, and it would be even better if you could find the universal one as well. Ultimately, people do try to choose universal things, but then the risk is that they end up choosing the wrong one. Maybe the thing that needs to happen is a shift in the willingness for infrastructure, or standards, to be re-evaluated. We need to be willing to bite the bullet on the cost of re-evaluating standards. Often I think the most exciting stuff I hear about regarding innovations is people challenging the standards.

- Anton: What was that example from machine learning, GPUs? If someone came up with a completely different way of doing it, that sounds really exciting. That could have these huge knock-on effects.

- Audience: The funniest one in real estate is that real estate is priced per square foot, not per cubic foot. That just doesn’t make sense. Every building is undervalued, structurally.

- Alec: On the point of re-evaluating standards. I wonder how the people using it can be responsible for it. Infrastructure is designed by people typically weighing cost or liability or content. For example, in schools, the artifact of classes and periods is much more reflective of the needs of the communicator than the experience of the learner. Infrastructure that looks more like “pull”— responsive— looks very different. It takes change in political economy.

- Anton: That’s crucial, right, it’s always political. There’s always some kind of power dynamic. Someone forces it on the rest of them… network effects, etc. Oftentimes its done by regulators. Hopefully you get some kind of conversation, but ultimately if you choose some kind of standard, it has to be imposed to a certain extent.

On names and definitions

- Liz: Katherine, to your point of creating your own names… I think the idea of naming is such a powerful idea because it represents so much of the subsystem within something, without having to now describe everything about that system. By creating these new names though… how have those subsystems broken down? How has it been challenging?

- Katherine: Well, it is jargon, so anyone coming onto the project has an onboarding cost. We even made our own terminology page.

- Katherine: Anton, I liked your point about the difference between domain-specific language and universal-language. I think what we’re doing is set-intersection, but yours is more of a set-union.

- Will: I am a consultant and so much of my time is spent with these different business units that are very specific. They have their own language. We spend hours working out what they’re talking about, then unpicking it. And rather than directly trying to establish some universal language, my goal is to try to describe it in a way that a child could understand it, basically. That’s the only way we can achieve universal accessibility. Even if you do have time savings from specific use of language.

- Katherine: A great piece of infrastructure is the Simple English Wikipedia

- Anton: There’s also that xkcd book, Thing Explainer. It only uses the top 1,000 most common words. I work with my PhD students to summarize what they’re doing with it. It’s very difficult. Invention isn’t even in there. “Make things better!”

- Liz (added afterwards): An excellent pairing to this conversation is The Information by James Gleick, chapter 2: The Persistence of the Word (There Is No Dictionary in the Mind)

Language drift

- Jacob: I think one interesting thing about language: The more users of it the more there’s drift. You can see this as a property of natural languages over time. The more languages used, the faster terms drift. I think this happens in technical jargon as well. If there’s a small number of users the terms can remain precise. But as soon as it reaches a broader technical community they start to become less precise. That at least has been my experience with machine learning. I think there are other fields that seem to maintain precision, but that takes very strong discipline and very strong norms.

- Alec: Do you think that’s based on the size of the group or the speed at which the group grew?

- Jacob: It could be about rapid growth, I think that’s a good point. I could imagine that if a group is big but grew slowly, there’d be less of that. I think there are incentives to stretch the meaning of terms— like if you want to say that you’re paper is about X then it’s convenient to redefine X slightly.

- Anton: Whenever any term gets popular, its meaning gets stretched. Like in economics, it happens all the time.

- Alec: Outside of the incentives problem, to the extent that we construct new language through analogy… if you’re in a sub-field that does in fact have a need for an idea that’s analogous to a different field, you might want to port that word.

Biology + Math, Incremental vs. Wholly New

- Katherine: It might be nice if there were a mathematical biologist in the room, because I think the idea of language drift ends up being very common in that field, when they import ideas into biology from math. But I’m not an expert…

- Several people look at Sasha

- Sasha: Was there a question about mathematical biologists? I was actually just talking with a guy at Berkeley doing very interesting work. He’s trying to find every paper about biology that has differential equations. And then harvest all of them and try to build a single model. Most biologists don’t really read that work. Maybe Gwern would have some thoughts about this too. A lot of what we’re seeing in biology could be influenced with the tools from mathematics, but a lot of people just aren’t interested in doing that.

- Long pause

- Gwern: Well don’t look at me!

- Liz: Sasha, when we were speaking before, you mentioned merging interests across culture, linguistics, and biology. And how–now that you see this play out in the real world, in the clinic–there are very real ways that you’ve seen this mapping happen.

- Sasha: Yeah, so… well I guess the idea that comes to mind is how thought and language are very tied together. Doctors just aren’t thinking about differential equations at all. It will never make it into their patients notes. Maybe a first or second year med student will have a little bit of concept of a half life. But beyond that, they’ll likely never see that again, unless they deal very closely with drugs or something. So I guess there are ways that these inefficiencies, or sub-optimalities… lead to things that doctors are not aware of.

- Sasha: Liz and I were talking yesterday on the bus, and I was proposing that a way around this would be to just collect a lot more raw data that wasn’t filtered by doctors. So you have both the doctors notes, or whatever they want to write, and then you would also have as many things as you can measure in the blood of the patient. There would be two parallel streams… one more computation, one in language that doctors can understand. The first branch doesn’t exist in current medical infrastructure.

- Liz: And thus, the proposal being, it’s not a whole new infrastructure, but an incremental change in infrastructure, a change to what people are already used to doing.

- Sasha. Right. Another way is to build that branch separately in something completely out of a clinical context. For example, you could build it into alternatives to the healthcare system. If it turns out to be useful— and it will be very shocking to me if it’s not useful— then we’d be able to merge it into the existing way of doing things.

Cultural Infrastructure first?

- Sasha: Are there any major infrastructural shifts in any areas that you’re aware of? An obvious thing that I think of with infrastructure is water management. Presumably, people had cultural practices built around major infrastructure, and then at some point a group of people decided to invest in capital to do something about it.

- Katherine: Sounds like you need cultural infrastructure first before you have actual infrastructure.

- Alec: My understanding is that municipal financing in the US came about because of water infrastructure. Cultural infrastructure was in place to then install the physical infrastructure.(A quick search on the internet explains that the first US municipal bond was issued in 1812 by the City of New York for water infrastructure— to construct canals from the Hudson River to Lake Erie and Lake Champlain)

- Liz: We’re at time, but one example to look into regarding water infrastructure and culture is an interesting town: Lijiang in Yunnan, China. The city was built up around their water system. It came out of their belief that water was a sibling to this ethnic group, the Naxi. As a result, they structured society around their water infrastructure: canals and springs throughout the village. At these springs located across the town, they constructed “three-pit” wells… series of three pools with strong rules for use. The first pool was to gather drinking and cooking water, this pool then flowed into a second pool for washing food, and this then flowed into a third pool for washing laundry. From these pools the water then drained into a series of canals that ran through the town. This construction also mapped to the time when the society did things. So that, in the early morning, they would draw water to drink. Later in the day, they cleaned vegetables. Then still later in the day, they’d do laundry. It’s a good example of cultural infrastructure mapped to physical infrastructure.

For more on water infrastructure and cultural infrastructure, check out Water by Steven Solomon

Thanks, all!